This post is a supplement to part 1 of the risk of bias in RCT series.

By allocating treatments in a truly random manner the known and unknown patient characteristics will balanced between treatment and control groups, especially for large sample sizes.

Readers of RCTs will recognize that there are different types of randomization schemes that are used. Here are the main four types.

Simple randomization = easiest, although imbalance may occur in small trials.

Simple randomization, or sometimes called unrestricted randomization, is when each trial participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any treatment group. This is similar to flipping a fair coin. It does not have to be an ‘equal’ chance but rather each participant is independently assigned to a treatment group using a predefined fixed probability.

One of the potential problems with simple randomization is that, by chance, there is an uneven number of patients randomized to the treatment and control groups. This is particularly notable is smaller sample sizes. To illustrate this, I ran a simple randomization allocation scheme in a 1:1 ratio for treatment and control groups for 60 participants. The left panel in the figure below shows 100 repeated trials with trial “87” labeled showing that 21 patients were assigned treatment. Therefore, 39 were assigned to the group group. The right hand panel shows the cumulative assignments to treatment and control groups over time to illustrate the imbalance over time.

One solution to this imbalance in the size of groups is to ‘restrict’ the randomization within blocks.

Block randomization = adds balance to treatment group size over time

Block randomization is a method to balance the size of the treatment groups over time. This is done by randomizing participants in blocks whereby within each block the desired ratio of participants in each group is maintained. For example, in a block of 4 with a treatment (T) and control (C) group randomized in a 1:1 manner. TTCC, TCTC, CTCT, CCTT.

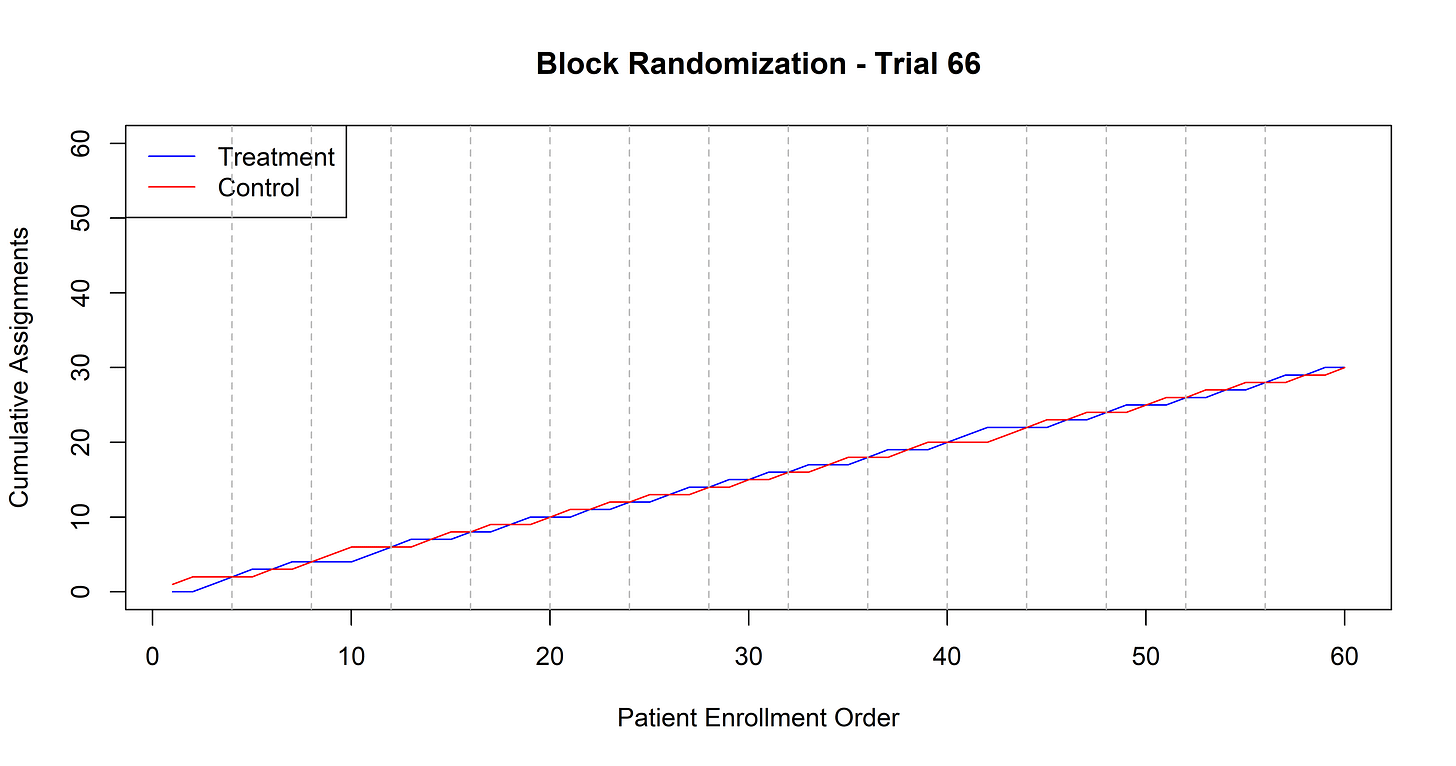

The main benefit of blocked randomization is group balance over time and thus improved statistical power. This is especially important in small trials. Here is a figure to illustrate this concept.

One risk of blocked randomization is that if the block size is known then the last allocation within each block is predictable. The ability to ‘know’ the treatment assignment can introduce bias. This problem can be avoided by using random permuted blocks which means the block size is varied in a random fashion.

Block randomization helps to balance the size of the treatment and control groups over time but what if you want to ensure balance for specific prognostic variables such as disease severity, sex, or a specific comorbidity. This brings us to stratified randomization.

Stratified randomization = balances key prognostic variables

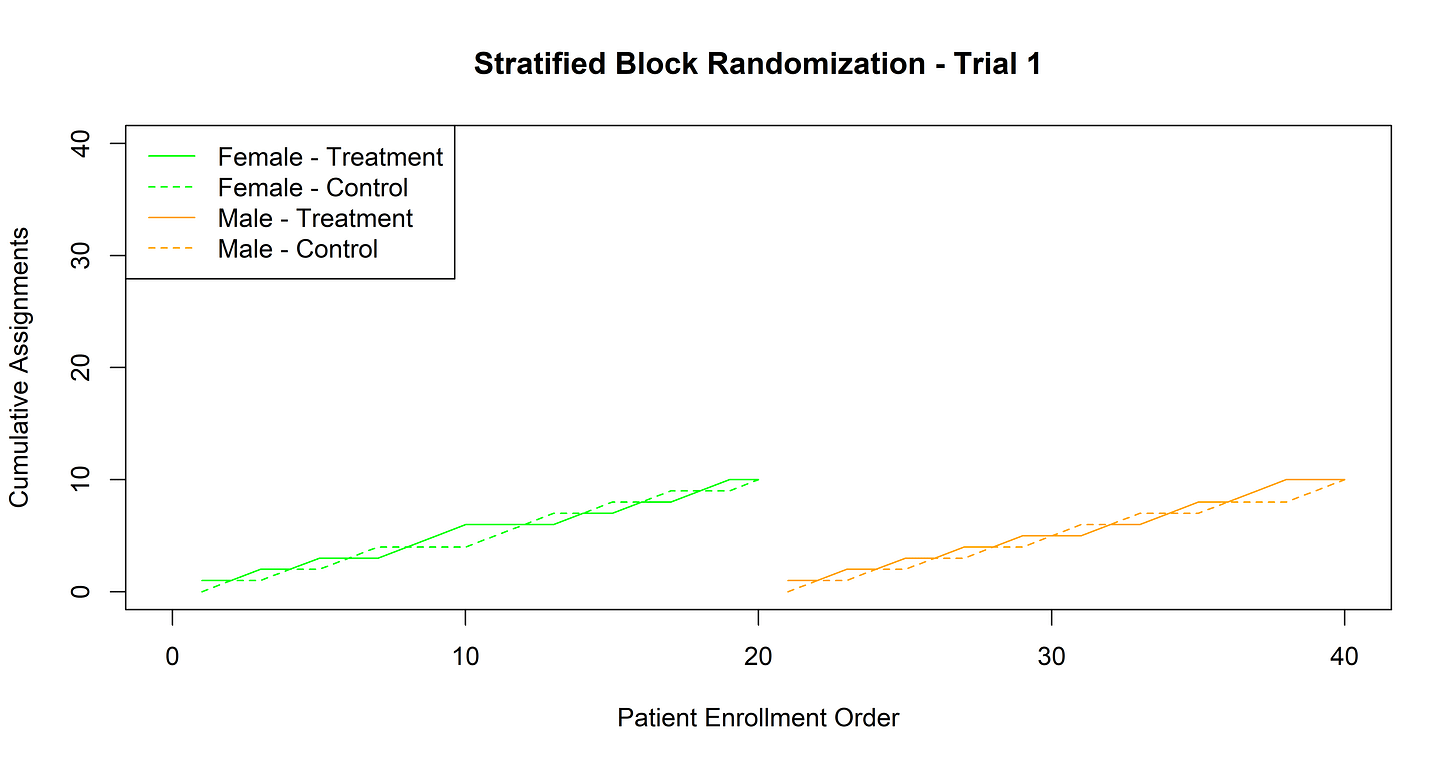

Stratified randomization is a type of restricted randomization where the randomization procedure is done separately in subsets of participants.

Generally, stratified randomization will be combined with blocked randomization to ensure that within each stratum there is a balanced number allocated to treatment and control groups.

Adaptive randomization = evolves as evidence accumulates

Adaptive randomization is different from the above in that the probability of being allocating to treatment or control changes over the trial. The probabilities may be adapted based on imbalance in group size, patient characteristics, or observed outcomes. The main purpose of this approach is to improve trial efficiency and sometimes address ethical concerns.